- Home

- Laurie Canciani

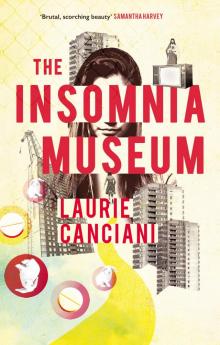

The Insomnia Museum

The Insomnia Museum Read online

THE INSOMNIA MUSEUM

Laurie Canciani

Start Reading

About this Book

About the Author

Table of Contents

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

About The Insomnia Museum

Anna lives in a flat with Dad. He is a hoarder, and together they have spent the last 12 years constructing the Insomnia Museum, a labyrinth built from dead TVs, old cuckoo clocks, stacks of newspapers and other junk Dad has found. Anna is 17. She can’t remember ever having seen outside the flat, but noises penetrate her isolated world: dogs bark in the walls, music plays in the floor, and a ship sails through the canyons between the tower blocks.

Then one day Dad falls asleep and won’t wake up, and Anna must leave the museum and try to survive in a place that turns out to be stranger and more dangerous than she could have imagined.

In this dazzlingly original debut novel, Laurie Canciani has created a world that is terrible, magical, and richly imagined.

Contents

Welcome Page

About The Insomnia Museum

Dedication

1 Quick Slow Time

2 The Insomnia Museum

3 Keeping Sound

4 Dorothy

5 I Know I Have a Heart

6 If I Were King

7 Crushing Poppies

8 Drowned Fish

9 Somewhere Over the Somewhere Else

10 Your Little Dog Too

11 Who Is Judy Garland?

12 See Sick

13 Pay No Attention to the Man Behind the Curtain

14 Emerald Green

15 Now in Technicolor

16 Toto the Dark Skinned Man

17 Emerald City

18 Witch Tin Woman

19 Hey Dee Dee

20 Dog on the Wall

21 Please Knock

22 The Good Kiss

23 The Passenger

24 Curtains

25 Tin Boy

26 Heart’s Desire

27 Twister Town

28 Sweet Street

29 There’s No Place Like

30 Fly My Pretty

31 Boy Broken

32 Surrender Dorothy

33 Simon Says

34 And You Were There

Acknowledgements

About Laurie Canciani

An Invitation from the Publisher

Copyright

For my mother Jayne Canciani

For Dom, always

For Jen, my fierce ally

This book is dedicated to Brian and Marilyn Richards,

who would’ve loved it.

1

Quick Slow Time

THE MAN PULLED the feathers away so he could get a better grip on the head. The girl sat next to him with her arm around his back and her eyes turned towards the hard work in his lap. She tried to follow the fall of the painted feathers as he plucked them one by one by one from the bird but they were caught too quick by the wind that broke through the letterbox and billowed against the wallpaper and settled into the darkest corners of the room.

Your hands are shaking, Dad.

The cuckoo clock was old. Its doors were warped and the nails that held it all together were forced in at crazy angles. He picked the black varnish off his fingernails and blew out and lifted the clock and placed it in his daughter’s lap. It was an effort to bring the thing home. It was a struggle to drag away parts of the world and think on them and the cutting and changing that must be done and it was hard to make the difference. It was an effort to do much of anything. Recent weeks he had fallen far into the chase again and his eyes gleamed like polished black eggs.

She teased the metal arm out through the doors again, locked her knees around the painted house, pulled the bird from its bed and held it between her legs. He smiled as she grabbed hold of the cheeks and twisted the head back and forth and all the way around until the skin creaked.

You’re doing it.

I know I am.

Ignore the broken eye.

I am.

Don’t let him scare you.

I’m not.

She drove her fingernails into the hole that had split the side of the bird’s neck and she hooked the head and pulled. The stitching drew back through each needle hole like a retreating snake and the head popped and ripped and the insides exploded out and then the whole head came off in her hand and the clock dropped from her lap and landed on the hard floor with the bird stuck headless on the end of the rocking metal arm.

Her father worried himself into more itching and scratching and shifting when he saw the blood welling where the beak pierced the skin on her palm. She didn’t like blood. She swayed when she saw it and grabbed hold of her stomach that had started to fold. He took the head and dropped it into one of the boxes and ripped the bottom of his black tee shirt and wiped away all the blood with the cloth and tied it three times around her hand until it was sopped and the sickness was righted.

She looked at him and he looked at her. The sound of the world was coming up through the plughole in the kitchen sink and echoing deep in the walls. There was a long howl. A siren. Dogs. Rain. Then the wind came in again and bobbed the head of Plastic Jesus who lived happy and useless on top of the broken Hi-Fi.

I’ll do this next part.

I know, Dad.

I always finish everything off.

You do. You’re good at that.

He pulled the small house onto his lap again and tweezed away the last of the wire and sponge and string that stuck out through the hole in the neck. The light spilled through the boards in long thin slats. She picked up the new head he had found that morning while he was out looking for white rabbits. Or looking for Mum. She looked at the head. It was made of plastic with fat pink lips and large blue sparkling eyes and blond hair that was curled around a lovely broken neck.

He took the head and held it against the hole in the neck of the bird and pierced the plastic with a needle and threaded string in and out and down into the empty chest cavity and back up again. He pulled the string tight and threaded it back through a loop and then out again and through another loop until the head was pulled tight to the body and the plastic face sat against the feathers as though it had been sitting there all along.

Oh Dad, it’s good.

He sat back and wiped his mouth with the end of his ripped tee shirt. They both looked at the work. Then he looked at her and kissed her face. His lips were dry.

Let it be, he said. It needs to get used to itself again.

What if he doesn’t like himself anymore?

He doesn’t have to like himself.

Why?

He just needs to accept that there’s no changing anything.

He pulled the clock to his chest and took a screwdriver from the arm of the chair and twisted it into the clock face that sat above the small doors where the creature was learning to be different. Somewhere outside something chimed and turned and the wind made an ache. It felt as though it had come from a long way away. Dad hummed a song from the seventies. She watched his mouth close around the sound and open again. He cranked the back of the clock and the hands spun around and around and settled crooked on a number. He brought a carrier bag of rusted nails and metal treasures from a box and fished in there for other numbers that he had ripped from other clocks in other houses that she had never seen. He pulled out the new numbers one and two and three and pressed them against the clock face and nailed them in place next to the digits that had been there since the clock was made in nineteen eighty something. He polished the numbers with his fingers and stuck his screwdriver into the middle of the clock and then he listened at the little doors fo

r the sound of.

What are you listening for?

He looked at her and she looked at him. He moved his face aside and slipped his hand around her head and pulled her to the little doors and hushed her lips with his fingers. She closed her eyes. She heard it. It was the beating heart of the bird.

Dad pointed to the numbers.

This one is a six, he said.

What’s that one?

A four.

And that?

Two.

This?

Fifteen.

Dorothy Gale was paused on the TV watching everything with sad homesick eyes. She turned back to the clock. She asked again and again what the numbers were and she closed her eyes.

This one?

Two. Three. Four. Twenty-six.

I can’t do it.

Yes you can.

I wanted to learn to read.

Telling time is better. It’s more useful.

Why?

Just listen.

He pointed to the numbers and talked about the hands and the clock face and the bird with the new face that would come out every hour if it was ready to be good and every five minutes if it felt like being bad. Depends on the clock. He told her that quarter past was as good as quarter to but not as kind as half past and he told her that there were thirty-nine hours in a day but the nights were shorter and that’s why they didn’t need much sleep.

There’s too much work to do.

I know.

He stepped away and fell back onto the settee and pulled his silky black hair out of his eyes and looked at the ceiling. Then he rummaged for she knew just what, and fell back into the long chase. He looked up and opened his mouth and sighed.

She kissed his cheeks and turned back to Dorothy who had been talking to her these last many days. She rewound the tape. Played it again. The video was old and the player was lazy and the tape chucked the film around and it stopped and started on the TV just like thoughts.

Look at my hands.

I see them, Dad.

Dorothy sang and the light through the slat shifted and spilled over the boxes of junk and stacks of newspapers and table legs and rails of old stamps and clothes and marble topped furniture and typewriters and old chipped cups and damp patches working up the walls and screws and piles of outside and her own face, too, that was fixed upon the dusty TV screen. The room shrank. Her hand throbbed under the tight threads of tee shirt. A little seed of claustrophobia was planted in her head and she sat in the middle of the room in the last of the light. The sound of the world was gone again and in an hour the bird would come out of the hole and squawk. And then there would be only the quiet and the dark and the man who chased rabbits and Dorothy and the bird and the nodding Plastic Jesus and all the junk in all the world broken apart and pressed against the walls of that lovely insomnia museum.

2

The Insomnia Museum

WHEN ARE WE going to be done?

Done with what?

Changing everything.

The world is big.

I haven’t seen it.

That’s because it’s not ready for you yet.

I love you, Dad.

I’m glad you do.

Do you love me too?

I love you more than all of it. And. I can’t think.

The sun peeped through the boards and cut her body into quarters. She played the tape and watched how Dorothy stepped from her dusty farm in Kansas to a world of Technicolor. Dad sat down on the settee and rolled her a smoke and lit it and she took it and smoked it and blew it all to the ceiling that was covered in waves of dust and spider’s webs. Dad straightened up on the settee and he leaned forward and scratched his forehead with the cigarette in his hand and the light zigzagging.

I’m going out again.

She looked at him. He was thinner than he had been and his skin was covered in blotches that worked their way from the medicine wounds in his arms to his neck and cheek and circled his fat lovely eye where he had recently begun to inject. She never liked it when he left her. She turned her body to his and picked at the holes in the carpet.

Why do you need to go?

I have to go and get more junk. If we bring in what’s on the outside and work on it we can make everything better. I’ll look for Mum too, if you want.

I don’t want to see her.

I’ll go looking for white rabbits then.

When she was five or six he boarded up the windows of the flat and locked the front door and began to bring home boxes of junk that he piled in towers that stretched from the carpet to the webbing and the lampshades that were blackened and yellowed by lovely smoke. In the rooms the towers grew and lined the walls and seeped into the middle and each room became a maze of junk and mess and artefacts stolen from the houses of others. She looked at the picture that hung between the boarded windows on the back wall of the living room opposite the bright TV screen. The picture was of an old woman with a severe face and grey hair and a smile that pulled her lips past the gums and teeth.

She asked him who the old lady was when he brought it here those months ago.

I think she died. They were clearing out the house and I pretended to be one of them and I walked in and looked around for money or whatever. That picture was hanging on a wall in the bedroom. I couldn’t take anything else. I wasn’t myself. She looked at me and I looked at her and I took her off the wall and hid her underneath my coat and I left and brought her here. Nobody wanted her. Don’t you think that’s sad?

He made a workshop in the attic with wooden tables and vices with two plates that twisted and screwed and held whatever junk he wanted to change. He took the junk out and brought home more and more until the walls were lined with phone books and magazines and newspapers that she couldn’t read and plastic jugs and pictures of families she would not know and metal taps and table legs and street signs. There were street signs everywhere. They were all different and the letters were big and small and spaced apart and scrunched together and she lifted one and looked at Dad but he had fallen too deep into the chase and his eyes were searching for God in the back of his head. She looked at the signs again. Kansas, they said.

*

Dad stuffed carrier bags into his shoes because he didn’t want the rain to get in. He took one shoe and looked inside and pushed the carrier bag in and turned the shoe around so that she could see. She looked at the holes in the bottoms of his shoes and she saw the white plastic pressed against the hole and she stuck her finger in and told him that it was good, Dad. It looks dry. Fine. He did the same in the other shoe and slipped them on his feet and she could hear the crackle of the bag and then nothing when his feet were flat against the sole.

When will you be back?

He stood up and went past the boxes and took the clock from the mantle and brought it back to her and pointed at the hands. He told her he would be back when this hand was. And the other hand was. About two hours and forty-five minutes and if the mad bird doesn’t keep the right time he’ll take off its plastic head.

Don’t do that, Dad.

He kissed her face and asked if she would get to work on the jewellery box that had no dancer and she told him that the music always made her feel sick. He went into the kitchen that was at the other end of the living room and separated by a washing machine and a unit and a stack of antique walking sticks that always tripped her when she walked by them. He filled a glass with water and came back again and handed the glass to her and told her to drink the whole thing whenever she felt the sickness come.

I will.

Good.

How long will you be?

I told you already.

I just want to make sure you remember it.

He put on two coats and lifted one of the hoods and he went out of the room and into the hallway and slipped past the stacks and past the ladder that went to the attic and then he went off into a place she couldn’t see. She heard the click and she smelled the wind and then she heard the ba

ng when the door closed then the whole place changed as it always did when half the life was gone.

3

Keeping Sound

DAD HAD BEEN gone for six hours.

He used to read to her before his vision started to go, before he started seeing silver worms where there was only a doorway or falling ribbons of wallpaper. When he told her about the worms, she told him that she could feel moths in her head and sometimes they gave her a nosebleed that lasted so long she thought her whole body would drain out and fill up the bath. He looked at her and blew the smoke out of his lungs.

Yeah but mine are real, he said.

He had been gone for six hours and she had missed him all that time. She worked on the jewellery box and watched The Wizard of Oz. She picked up the box and looked at the bottom and she shook it. There was a rattle that Dad had not noticed and she thought on that. She shook the box and stuck his screwdriver into a hole at the bottom and flicked the end and the bottom came away and something fell into her lap.

It was a round black tube with a gold ring around the middle and it was small enough to almost roll through the hole in the wooden floor beneath her. She caught it before it fell and she took it in her hands and looked at it in the small light that had crept in through the boards sometime during the last mad hour. She looked at the tube for a long time. Smelled it. Bit it. It smelled and tasted like plastic and there was a crack near the gold ring that she got her fingernail into and pulled and then the tube came apart in her hands.

Inside one half of the tube there was a red crayon and when she twisted the plastic base the crayon rose up and twisted out.

She went into the bathroom where the tiles were falling down and plaster was showing and there was a black garden growing along the wall. She turned on the light that hadn’t worked for years and years and she turned it off again. Sometimes she forgot what time it was. What year. Sometimes she thought she was five or six again and the halls were clean and the lights were working and the windows were full of light. Sometimes she forgot that he had become an old man. She thought of the way his face changed and she felt. Something. Guilt. It was as though she had grown up too quickly and stolen the years from Dad and now that she was a woman, seventeen, he was old and pressed up against the ceiling, dangerously close to being as old as he would ever be. Sometimes she looked at him. She stared at him for. And then she was weighted to the threads in the carpet. Once death was done with him it would look at her and she would not be ready to look back.

The Insomnia Museum

The Insomnia Museum